By Paige Hua

Daily Bruin, April 21, 2019

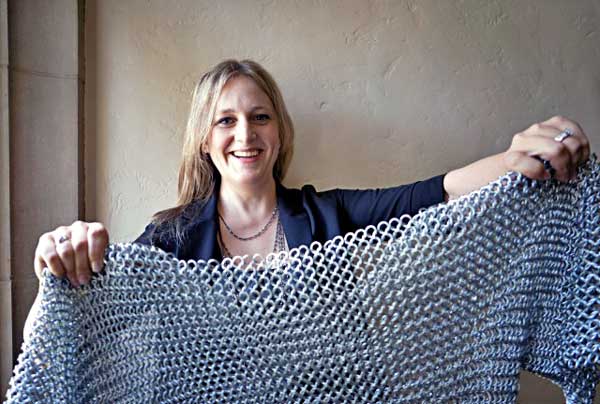

Objects are more privileged than subjects, Sara Burdorff suggests in UCLA’s next Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies Roundtable.

Typically, men in Anglo-Saxon literature are viewed as the subjects – nonmarginalized, active players. Women, on the other hand, are interpreted as passive objects, but Burdorff said she aims to challenge these conventional norms.

Over the course of 25 years, UCLA’s CMRS has solidified the Roundtable talks as a campus tradition. The Roundtable will welcome Burdorff, an alumna and early medieval literature CMRS affiliate, as their newest speaker in Royce Hall on Monday. Burdorff will discuss her latest project, which explores women and their roles in both Old English poetry and medieval society.

Burdorff said her presentation reads against the grain and casts women in a new, unconventional light. Rather than arguing that women are objectified within the traditional medieval system, Burdorff said she will analyze women’s crucial roles in a society of male warriors.

“It’s our instinct to assume that the active male subject is in a privileged position,” Burdorff said. “But I’m looking at the suggestion that the objects were more privileged than the male subjects.”

To expand upon this idea, Burdorff said she is referencing women in works such as “Beowulf” and “The Wife’s Lament,” in which the women are often defined by the objects they wore rather than personality. The women donned golden rings and bejeweled necklaces, which Burdorff said, from a modern perspective, can be interpreted as objectification.

But in Burdorff’s interpretation, women in Old English fictional societies were allowed to transcend the system that demanded men provide the gold; the warriors’ status depended upon their ability to keep the precious metal circulating within society. Poetry, however, presented the women as being closer to the beautiful objects since they wore them on their bodies as jewelry, Burdorff said.

By doing so, women were symbolically not the objectified figure because they wore the gold that defined the purpose of the warrior lifestyle – passing gold on from one generation to the next, Burdorff said.

“The masculine subject spends a lot of time investing himself in these objects that will outlast him,” Burdorff said. “My suggestion is that women are much closer to these objects that are preferable to a limited human life span than men are, giving them more privilege and resonance.”

Women are allowed to keep the gold while the men are expected to circulate the metal within the economy, Burdorff said. And for the pre-Christian world, Burdorff said gold lasted much longer than people; it was as close to immortality as they could get – and women were the ones who could enjoy it.

“Women embody the gold and they are survivors of the violence that takes the men in these societies so repeatedly,” Burdorff said. “I think the tangible weight of a beautiful gold object is something that transcends time and expectations.”

For Burdorff, the project, like many presented at the CMRS Roundtable, is still a work in progress, which allows people the opportunity to present works prior to completion, said Karen Burgess, the CMRS assistant director. In workshopping their ideas, Burgess said, speakers can receive feedback from their colleagues or even discover missing pieces of information from students in attendance. The first draft is never a finished product, Burgess said, and for Burdorff to expose her work to other scholars of the Medieval and Renaissance eras is to strengthen her final research project.

Through discussing her project, Burdorff said she hopes attendees gain a willingness to question traditional interpretations of literature. Foundational assumptions, though often presented as fact, are more debatable than they seem, she said, and the presumed patterns, such as the objectification of women, are still open for discussion.

“There’s something very exciting about going back to pieces that have existed for so long and still being able to find new combinations and new patterns that add to our understanding of the Anglo-Saxon mindset,” Burdorff said.

In regard to finding new patterns in pre-existing literature, Joseph Nagy, a professor emeritus for the English department, said he agrees with Burdorff, supporting her choice in revisiting and finding ways to redefine the past. Nagy said it makes sense in the context of Anglo-Saxon culture that to be bright and ring-decked is to be above others. Burdorff’s interpretation is an example of how we can challenge the fictional assumptions of present-day literature, Nagy said.

“It’s fascinating that she is going at the idea of female characters being the metric by which heroes and heroism is to be measured,” Nagy said.

The Roundtable often features an array of unconventional ideas that move the studies of the Medieval and Renaissance eras forward in one direction or another, Burdorff said. It is the ideal place to challenge people’s initial instincts to render women as automatically inferior, she said.

“These women are actually intrinsic to the heroic economy,” Burdorff said. “Objects can self-signify and outlast humans by a great extent, and it was the women who were brought closer to that level.”