Imagine this: You’re 17 and have never left home. Your father and uncle, merchants who have been absent your whole life, return home before they set off again on their next trip. Only this time, you join them.

The journey will cover 15,000 miles (24,000 km) and last 24 years. You’ll see things you could not have imagined and be catapulted into the upper echelons of a powerful empire. And, eventually, you’ll become one of the most famous travelers in Western history.

What could be the outline for a blockbuster movie is nothing less than the biography of Marco Polo.

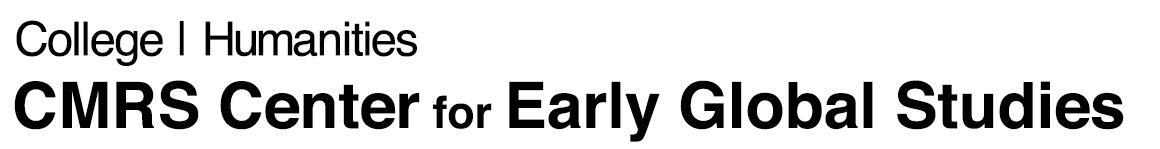

Born in Venice in 1254, Polo traveled the Silk Road, a medieval trade route connecting Europe to Asia, between 1271-95, spending 17 of those years in China as a prominent figure in the flourishing Mongol Empire under Kublai Khan.

After returning to Italy, Polo collaborated with the writer Rustichello da Pisa to chronicle his journey. The resulting book, “Il Milione” (The Million), known in English as “The Travels of Marco Polo,” eventually became a medieval bestseller. It was translated into numerous languages and read by everyone literate, from princes to priests; Christopher Colombus was said to have carried around a copy.

An account that ‘shocked’ Europeans

Polo was far from the first European to travel to medieval China, let alone the first individual to document this. According to Hyunhee Park, a professor of history at City University of New York, Muslim travelers were documenting both land and sea voyages to China as early as the 9th and 10th centuries. But at a time when Europe was closed and inward-looking, Polo was the first European to bring information on China into the general consciousness — and his report did not meet European expectations.

Polo described the Mongol Empire as a great civilization with great cities, Park explained: “Many Europeans were shocked. [He] was even criticized as a liar.”

Polo’s descriptions deviated from the conventions used by other Westerners who reported on non-European lands, explains Margaret Kim, a professor of foreign languages and literature at National Tsing Hua University in Taiwan.

“Before and even after Marco Polo, European travel writers, when they describe foreign places and foreign people, they teach moral lessons and religious doctrine. That’s implicit in what they write. But Polo doesn’t have that kind of sense of religious doctrine … He seems primarily, in his descriptions, interested in landscapes and customs of different parts of the world. He’s a very secular person.”

Employing the ‘Imperial Gaze’

Polo’s view sets him apart from future European travel accounts, which were largely driven by a desire to conquer and a perspective of civilizational superiority.

“Marco was amazed by the wealth and power of the Mongol rulers at a time when the East was fabled to be rich and prosperous in comparison with medieval Europe, so his attitude was very different from later European explorers and militant colonialists,” said Zhang Longxi, distinguished professor at Yenching Academy of Peking University, explaining that future descriptions of China would label it “backward” and “stagnant,” nothing near the grandeur of Europe.

In China, Polo became a well-respected figure in Khan’s court. While his exact position remains debated, there’s a broad consensus that he was a prominent civil servant with diplomatic responsibilities. He therefore looked at the Mongol Empire not as a foreigner, but as an insider.

“[Marco] left Venice as a teenager and spent the most formative middle years of his life in Asia. It’s there in Asia that he developed his way of thinking about the world that cannot be characterized as purely Western,” Kim explains. “But he does have what I would call an ‘Imperial gaze’ … He viewed the world as divided between the more or less civilized peoples of the world. So in Marco Polo’s world, you’re either very civilized, somewhat civilized, or savage.”

And for him, as Kim points out, the greatest center of civilization was not the one Europeans expected, but rather: Kublai Khan’s Mongol Empire.

The many different travels of Marco Polo?

As a source of historical information, Polo has had his fair share of controversy, much of it based on complexities surrounding his book.

There is no one authoritative manuscript; instead, some 140 different versions exist. The role of Marco Polo’s co-writer Rustichello in the book’s production and his possible influence on its content also adds a layer of uncertainty viewed differently by historians.

Kim considers Polo to be the author of the book, responsible for its content and style, and believes Rustichello may have overseen the copying and dissemination.

Zhang, however, believes that while Polo was the source of information, Rustichello may have shaped the book’s content: “Rustichello, a romance writer, actually retold the stories from Marco, likely with added fantastic colors and details that would appeal to medieval readers,” he explained. Yet, the expert added, compared with some other works of travelogue literature from that period, “The Travels of Marco Polo” definitely shows restraint in terms of imaginary features.

Omissions of expected information on China and a purported lack of corroborating sources also led some historians, such as the prominent Sinologist Frances Wood, to question the authenticity of Polo’s observations. Yet today, historians tend to agree that Polo’s key observations are so original and so specific, they couldn’t have been made up, or solely be based on second-hand accounts — even though Polo/Rustichello make clear in their book’s prologue that they too include second-hand observations in their travelogue.

Scholars, including Park, have also found corroborating proof of Polo’s observations, including in primary documents coming from Chinese and Islamic sources, such as in the writings of Ibn Batutta, the celebrated 14th-century North African explorer.

Marco Polo: A man for today

Today, 700 years after his death, Marco Polo remains remarkably well-known, even by non-scholars: an American swimming pool game, an upscale fashion company, numerous travel businesses, even the “Snapchat for boomers” all make use of his famous name.

Yet Polo’s relevance goes far beyond his branding power.

For Kim, Polo shows that “the world contains things beyond our imagination of it in ways that may unsettle and disturb, but we can adapt to that. So the ‘Imperial Gaze’ is not the property of any culture or civilization. And it is certainly not the sole property of the West.”

As for Zhang, Polo provides a reminder during times of heightened tensions between much of the West and China that non-antagonistic cultural relations are possible: “Marco Polo offers an alternative model of East-West encounters and interrelations that are extremely valuable for us in today’s world. It is a model of mutual understanding and cooperation, rather than [of] fierce rivalry and conflict.”

Edited by Elizabeth Grenier