Organized by Jessica Goldberg (History, UCLA) and Luke Yarbrough (Near Eastern Languages and Cultures, UCLA).

Funding for this conference is provided by the Armand Hammer Endowment for the UCLA Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies and the UCLA Center for Near Eastern Studies.

This conference investigates how law shaped the boundaries of communities in the early medieval period in the Byzantine, Islamic, and European worlds, and how shifting notions of identity and belonging re-shaped legal discourses in their turn. To spur cross-disciplinary discussion, presentations will center around participants’ chosen selections of source texts, which will be pre-circulated.

It is by now a well-entrenched story that a part of the profound transformation of the late antique world was the re-defining of social belonging. Religious belonging increasingly became both a practical and legal marker of community, edging out the formerly prominent civic, ethnic, and political identities of the ancient world. Constantine’s edict allowing the transfer of litigants’ cases to the bishop’s court is often taken as a key moment in this transformation, in which part of the state’s legal and administrative prerogatives were transferred to religious authorities. Religious communities in turn developed (or expanded) legal systems as part of the services they offered (and the control they exerted over) their members. The overall change was echoed in the fabric of cities themselves, as by the fifth and sixth centuries, former civic spaces were often filled by other buildings, while new central spaces grew up around grander religious structures. The Arab-Islamic conquest is often seen as accelerating this process in the lands it incorporated, initiating a new legal tradition and explicitly granting non-Muslim religious communities rights of autonomous jurisdiction over their own affairs.

A number of scholars are currently adding nuance and complexity to some parts of this story as it moves from late antiquity to the early middle ages, while simultaneously challenging other parts of the narrative. Some are revising our ideas about how and why bodies of religious law were created. They study the process and personnel of generating and compiling legal materials, the intellectual rationales for defining religion as involving a body of normative law, and the role of state administration as promoter of this law. Other scholars have been delving into administrative documents to uncover the practical relations between communal leaders and institutions and state officers, demonstrating that narratives of communal autonomy in the Islamic world, like narratives of ‘immunity’ in the Christian West, radically under-estimate the role of states and of non-clerical communal elites. Still others have been re-examining the early medieval bounding of religious knowledge, which took place not only through the production of experts and expertise, but also by a process of erasing the traces of others’ scriptures and practices from their own textual corpora.

This conference attempts to bring a number of these scholars together into new conversations. In some areas, such as documents and institutions, there has been productive exchange between scholars of the Islamic and western Christian worlds, but this has been less true of other fields, like canon and Islamic law. Temporally, we try not only to bring together late antiquity and the early middle ages, but also to include several scholars of the later medieval period to help reflect on both subsequent developments and the afterlife of the communal constructs forged in the early middle ages.

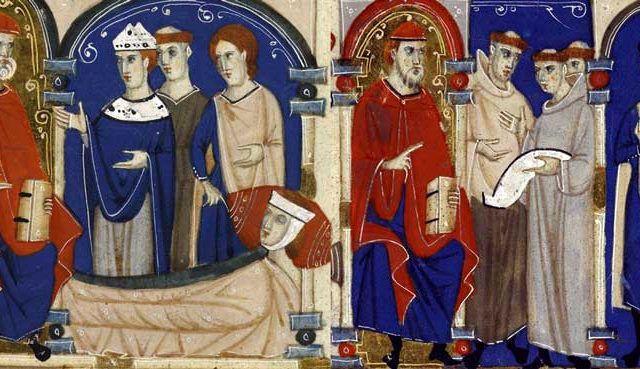

Image, top of page: Preliminary drafts of petition to the Fatimid caliph al-Mustanṣir (11th c. CE). Cambridge University Library, T-S Ar. 30.278, recto. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.